A Glimpse of Cambridge of the Orient

In his book Notes of Trips in Yunnan (written in 1941), the famous Chinese writer Lao She (1899–1966) called Xizhou the “Cambridge of the Orient.” How did Xizhou earn this title? Let’s visit this little ancient town and get a glimpse of its stunning beauty.

Journeying north along the Dali–Lijiang Highway, the Cangshan Mountains filled the view on the west side of the road, while the east side was the mirror-like Erhai Lake. Between the green and blue tableau was a wisp of pure white: my first glimpse of Xizhou.

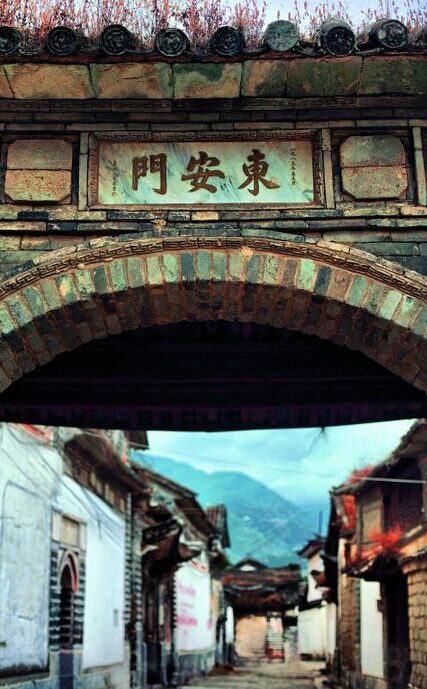

Xizhou has no city walls but it has gates. Entering through the west gate, one sees the structure of the Zhengyi Gate (the Gate of Righteousness), which is constructed in a pavilion style. Facing east from Zhengyi Gate, one sees a road which stretches onwards as far as the eye can see. Both sides are uniformly lined by more than a dozen white-walled courtyard homes with jet-black roofs, all facing east, as though the structures were constructed according to one master plan. Traditional logic holds that, having experienced centuries of wind and rain, the white walls should long ago have become mottled; yet, the walls here shine like new because any time the building facades are damaged, the owners quickly come to make repairs and the walls are frequently white-washed. Is this, then, what Lao She saw when he first set foot here, so long ago?

Xizhou has no city walls but it has gates. Entering through the west gate, one sees the structure of the Zhengyi Gate (the Gate of Righteousness), which is constructed in a pavilion style. Facing east from Zhengyi Gate, one sees a road which stretches onwards as far as the eye can see. Both sides are uniformly lined by more than a dozen white-walled courtyard homes with jet-black roofs, all facing east, as though the structures were constructed according to one master plan. Traditional logic holds that, having experienced centuries of wind and rain, the white walls should long ago have become mottled; yet, the walls here shine like new because any time the building facades are damaged, the owners quickly come to make repairs and the walls are frequently white-washed. Is this, then, what Lao She saw when he first set foot here, so long ago?

Time here seems fixed, unchanging. The residences lining the street are both ornate and orderly: all arranged in either the “three buildings, one screen wall” or “four houses, five patios” style. The so-called “three houses, one screen wall” is, obviously, comprised of three houses and one screen wall. The screen wall is a wall erected within the main gate of the complex for privacy. The screen is white and is also a unique architectural feature influenced by China’s fengshui theory. It surrounds the courtyard and also acts as the courtyard wall. The screen is inscribed with writing. The “four houses, five patios” consists of central courtyards and four patios, each similar to the Chinese character jing (井, which literally means a well water is drawn from), with the intersection of each patio forming a larger courtyard, creating four small patios and one central courtyard, for a total of five.

At the eastern end of Xizhou’s Shishang Street, there is a public square surrounded by shops, which is home to a large concentration on traders and merchants. In today’s era of tourism, such merchants are a common site, yet the town is home to a surprising number of old shops and one can readily see that the area has long been home to a developed commercial culture.

Not far from the public square, one can stay at the Dongyuan compound, constructed by the merchant Dong Wanchuan. The Dong clan has been in business since the Qing Era (1636–1912) and, by the time this building was constructed, they had already established themselves as a wealthy and powerful merchant family.

Not far from the public square, one can stay at the Dongyuan compound, constructed by the merchant Dong Wanchuan. The Dong clan has been in business since the Qing Era (1636–1912) and, by the time this building was constructed, they had already established themselves as a wealthy and powerful merchant family.

The Dong compound occupies an area of approximately twenty mu (15 mu is equal to 1 hectare), faces east, and consists of both a “three houses, one screen wall” structure together with a “four houses, five patios” structure. The courtyards within the compound are filled with rare and exotic flora and incorporate a Western style arch capable of handling automobile traffic. The timbers used to construct the structure are all superior woods such as toon and nanmu. The black-lacquered main gate is over 4 m tall. Each door weighs several hundred pounds and is comprised of a single slab of toon. The compound’s screen walls are approximately 10 m tall, displaying the wealth and power of its owner.

The Dong compound occupies an area of approximately twenty mu (15 mu is equal to 1 hectare), faces east, and consists of both a “three houses, one screen wall” structure together with a “four houses, five patios” structure. The courtyards within the compound are filled with rare and exotic flora and incorporate a Western style arch capable of handling automobile traffic. The timbers used to construct the structure are all superior woods such as toon and nanmu. The black-lacquered main gate is over 4 m tall. Each door weighs several hundred pounds and is comprised of a single slab of toon. The compound’s screen walls are approximately 10 m tall, displaying the wealth and power of its owner.

With its luxurious yet delicate architecture, bustling streets and warm inhabitants, it is no wonder that Lao She was moved to call this orderly little town the Cambridge of the Orient.

You will only receive emails that you permitted upon submission and your email address will never be shared with any third parties without your express permission.