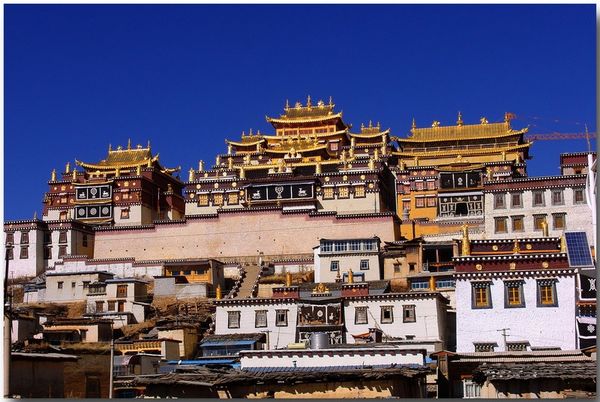

(Gadan Songzanlin Lamasery)

The Tibetan expression of Buddhism (sometimes called Lamaism) is the form of Mahayana Buddhism that developed in Tibet and the surrounding Himalayan region beginning in the 7th century CE.

Tibetan Buddhism incorporates Madhyamika and Yogacara philosophy, Tantric symbolic rituals, Theravadin monastic discipline and the shamanistic features of the indigenous religion, Bön. Among its most unique characteristics are its system of reincarnating lamas and the vast number of deities in its pantheon.

Tibetan Buddhism is most well-known to the world through the office of the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual and political leader of Tibet and the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. Historically, "Tibet" refers to a mountainous region in central Asia covering 2.5 million sq km. Today, "Tibet" officially refers to the Tibetan Autonomous Region within China, which is about half the size of historical Tibet.

Tibet remained independent until the early 1900s, when it was occupied first by Britain and then China. The Tibetans reasserted their independence from China in 1912 and retained it until 1951, when it was "liberated" by China. Today, Tibet is still occupied by China. The Dalai Lama, the spiritual and political leader of the Tibetan people, lives in exile in India, and Chinese officials outnumber Tibetans in their own homeland. Certain Buddhist scriptures arrived in southern Tibet from India as early as 173 AD during the reign of Thothori Nyantsen, the 28th king of Tibet. During the third century the scriptures were disseminated to northern Tibet. The influence of Buddhism was not great in Tibet, however, and was not yet in its characteristic Tantric form, for the earliest Tantras had just begun to be written in India.

The first significant event in the history of Tibetan Buddhism occurred in 641, when King Songtsen Gampo (c.609-650) unified Tibet and took two Buddhist wives (Princess Wencheng from China and Princess Bhrikuti Devi from Nepal). Before long, King Gampo made Buddhism the state religion and established a network of 108 Buddhist temples across the region, including the Jokhang and Ramoché temples to house the Buddha statues his wives had brought as their dowries. Conflict with the former national religion, Bön, however, would continue for centuries.

The most important event in Tibetan Buddhist history was the arrival of the great tantric mystic Padmasambhava in Tibet in 774 at the invitation of King Trisong Detsen. It was Padmasambhava (more commonly known in the region as Guru Rinpoche) who merged tantric Buddhism with the local Bön religion to form what we now recognize as Tibetan Buddhism. In addition to writing a number of important scriptures (some of which Tibetan Buddhists believe he hid for future monks to find at the right time), Padmasambhava established the Nyingma school from which all schools of Tibetan Buddhism are derived.

Tibetan Buddhism exerted a strong influence from the 11th century AD among the peoples of Central Asia, especially in Mongolia and Manchuria. It was adopted as an official state religion by the Mongol Yuan dynasty and the Manchu Qing dynasty of China.

Tibetan Buddhism spread to the West in the second half of the 20th century as many Tibetan leaders were exiled from their homeland. Today, Tibetan religious communities in the West consist both of refugees from Tibet and westerners drawn to the Tibetan religious tradition.

Between the 11th and 14th centuries, the Tibetans translated every available Buddhist text into Tibetan. Today, many Buddhist works that have been lost in their original Sanskrit survive only in Tibetan translation.

The Tibetan Buddhist canon is a loosely defined list of sacred texts recognized by various sects of Tibetan Buddhism, consisting of more than 300 volumes and many thousands of individual texts. In addition to earlier foundational Buddhist texts from early Buddhist schools, mostly the Sarvastivada, and mahayana texts, the Tibetan canon includes Tantric texts.

The Tibetan Canon underwent a final compilation in 14th Century by Bu-ston (1290-1364). It is divided into two parts:

- The Bka'-'gyur or Kanjyur ("Translated Word"), consists of canonical texts. The Kanjyur is made up of 98 volumes containing some 600 texts. The first printing of the Kanjur occurred not in Tibet, but in China (Beijing), and was completed in 1411. The first Tibetan edition of the Kanjur was at sNar-tang in 1731.

- The Bstan-'gyur or Tenjyur ("Transmitted Word"), consists of semi-canonical commentaries and treatises by Buddhist masters. The Tenjyur contains 3626 texts in 224 volumes, divided as follows:

- Sutras: 1 volume; 64 texts.

- Commentaries on the Tantras: 86 volumes; 3055 texts.

- Commentaries on Sutras; 137 volumes; 567 texts.

The most famous Tibetan Buddhist text is the Bardo Thodol ("liberation through hearing in the intermediate state"), popularly known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The Bardo Thodol is a funerary text that describes the experiences of the soul during the interval between death and rebirth called bardo. It is recited by lamas over a dying or recently deceased person, or sometimes over an effigy of the deceased. It has been suggested that it is a sign of the influence of shamanism on Tibetan Buddhism.

The Bardo Thodol actually differentiates the intermediate states between lives into three bardos (themselves further subdivided). The chikhai bardo ("bardo of the moment of death") features the experience of the "clear light of reality," or at least the nearest approximation to it of which one is spiritually capable. The chonyid bardo ("bardo of the experiencing of reality") features the experience of visions of various Buddha forms (or, again, the nearest approximations of which one is capable). The sidpa bardo ("bardo of rebirth") features karmically impelled hallucinations which eventually result in rebirth.

The Bardo Thodol also mentions three other bardos: those of "life" (or ordinary waking consciousness), of "dhyana" (meditation), and of "dream." The "six bardos" together form a classification of states of consciousness into six broad types, and any state of consciousness forms a type of "intermediate state" - intermediate between other states of consciousness.

In common with Mahayana schools, Tibetan Buddhism includes a pantheon of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and Dharma protectors. Arya-bodhisattvas are able to escape the cycle of death and rebirth but compassionately choose to remain in this world to assist others in reaching nirvana or buddhahood. Dharma protectors are mythic figures incorporated into Tibetan Buddhism from various sources (including the native Bön religion, and Hinduism) who are pledged to protecting and upholding the Dharma. Many of the specific figures are unique to Tibet.

For more information on Tibetan beliefs, see the articles on the Five Dhyani Buddhas, the wrathful deities, and Tara.

Non-initiates in Tibetan Buddhism may gain merit by performing rituals such as food and flower offerings, water offerings (performed with a set of bowls), religious pilgrimages, or chanting prayers (see prayer wheels). They may also light butter lamps at the local temple or fund monks to do so on their behalf.

In Bhutan, villagers may be blessed by attending an annual religious festival, known as a tsechu, held in their district. In watching the festival dances performed by monks, the villagers are reminded of Buddhist principles such as non-harm to other living beings. At certain festivals a large painting known as a thongdrol is also briefly unfurled — the mere glimpsing of the thongdrol is believed to carry such merit as to free the observer from all present sin.

Tantric practitioners make use of rituals and objects. Meditation is an important function which may be aided by the use of special hand gestures (mudras) and chanted mantras (such as the famous mantra of Avalokiteshvara: "om mani padme hum").

A number of esoteric meditation techniques are employed by different traditions, including mahamudra, dzogchen, and the Six yogas of Naropa.

Qualified practitioners may study or construct special cosmic diagrams known as mandalas which assist in inner spiritual development. A lama may make use of a variety of ritual objects, each of which has rich symbolism and a ritual function.

Another important ritual is the Cham, a dance featuring sacred masked dances, sacred music, healing chants, and spectacular richly ornamented multi-colored costumes. Mudras are used by the monks to revitalize spiritual energies which generate wisdom, compassion and the healing powers of Enlightened Beings. With accompanying narration and a monastic debate demonstration, the program provides a fascinating glimpse into ancient and current Tibetan culture. However, due to China's occupation of Tibet, this ritual is now forbidden.

There are four principal schools within modern Tibetan Buddhism:

Nyingmapa ("School of the Ancients") is the oldest of the Tibetan Buddhist schools and the second largest after Geluk. The Nyingma school is based primarily on the teachings of Padmasambhava, who is revered by the Nyingma school as the "second Buddha." Padmascambhava's system of Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism was synthesized by Longchenpa in the 14th century. The distinctive doctrine of the Nyingma school is Dzogchen ("great perfection"), also known as ati-yoga (extraordinary yoga). It also makes wide use of shamanistic practices and local divinities borrowed from the indigenous, pre-Buddhist Bon religion. Nyingma monks are not generally required to be celibate.

Kagyüpa ("Oral Transmission School"; also spelled Bka'-brgyud-pa) is the third largest school of Tibetan Buddhism. Its teachings were brought to Tibet by Marpa the Translator, an 11th century Tibetan householder who traveled to India to study under the master yogin Naropa and gather Buddhist scriptures. Marpa's most important student was Milarepa, to whom Marpa passed on his teachings only after subjecting him to trials of the utmost difficulty. In the 12th century, the physician Gampopa synthesized the teachings of Marpa and Milarepa into an independent school. As its name indicates, this school of Tibetan Buddhism places particular value on the transmission of teachings from teacher to disciple. It also stresses the more severe practices of hatha yoga. The central teaching is the "great seal" (mahamudra), which is a realization of emptiness, freedom from samsara and the inspearability of these two. The basic practice of mahamudra is "dwelling in peace," and it has thus been called the "Tibetan Zen." Also central to the Kagyupa schools are the Six Doctrines of Naropa (Naro Chödrug), which are meditation techniques that partially coincide with the teachings of the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Sakyapa is today the smallest of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It is named for the Sakya ("Gray Earth") monastery in sourthern Tibet. The Sakya monastery was founded in 1073 by abbots from the Khön family. The abbots were devoted to the transmission of a cycle of Vajrayana teachings called "path and goal" (Lamdre), the systemization of Tantric teachings, and Buddhist logic. The Sakyapa school had great political influence in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Gelugpa (or Dge-lugs-pa or Gelukpa, "School of the Virtuous"), also called the Yellow Hats, is the youngest of the Tibetan schools, but is today the largest and the most important. It was founded in the late 14th century by Tsongkhapa, who "enforced strict monastic discipline, restored celibacy and the prohibition of alcohol and meat, established a higher standard of learning for monks, and, while continuing to respect the Vajrayana tradition of esotericism that was prevalent in Tibet, allowed Tantric and magical rites only in moderation." {1} Practices are centered on achieving concentration through meditation and arousing the bodhisattva within. Three large monasteries were quickly established near Lhasa: at Dga'ldan (Ganden) in 1409, 'Bras-spungs (Drepung) in 1416, and Se-ra in 1419. The abbots of the 'Bras-spungs monastery first received the title Dalai Lama in 1578. The Gelugpa school has held political leadership of Tibet since the Dalai Lamas were made heads of state by the Mongol leader Güüshi Khan in 1642.

The Dalai Lama is the head of the dominant school of Tibetan Buddhism, the Gelugpa (or Yellow Hats). From 1642 to 1959, the Dalai Lama was the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet. Until the Chinese takeover in 1959, the Dalai Lamas resided in Potala Palace in Lhasa in the winter and in the Norbulingka residence during summer.

The current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is the 14th in a line of succession that began with Gendün Drub (1391–1475), founder and abbot of Tashilhunpo monastery (central Tibet). He and his successors came to be regarded as reincarnations (tulkus) of the bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvara.

The second head of the Gelugpa order, Gendün Gyatso (1475–1542), was the head abbot of the Drepung monastery on the outskirts of Lhasa, which became the principal seat of the Dalai Lama.

His successor, Sönam Gyatso (1543–88) received from the Mongol chief Güüshi (Altan) Khan the honorific title ta-le (Anglicized as "dalai") in 1578. Ta-le is the Mongolian equivalent of the Tibetan rgya-mtsho, meaning "ocean," and suggests breadth and depth of wisdom. The title was applied posthumously to the abbot's two predecessors. The Tibetans themselves call the Dalai Lama Gyawa Rinpoche ("Precious Conqueror"), Yeshin Norbu ("Wish-fulfilling Gem"), or simply Kundun ("The Presence").

The fourth Dalai Lama, Yönten Gyatso (1589–1617), was a great-grandson of Altan Khan and the only non-Tibetan Dalai Lama.

The next Dalai Lama, Losang Gyatso (1617–82), is commonly called the Great Fifth. He established, with the military assistance of the Khoshut Mongols, the supremacy of the Gelugpa sect over rival orders for the temporal rule of Tibet. During his reign the majestic winter palace of the Dalai Lamas, the Potala, was built in Lhasa.

The sixth Dalai Lama, Jamyang Gyatso (1683–1706), was a libertine and a writer of romantic verse, not well-suited to his position. He was deposed by the Mongols and died while being taken to China under military escort. The seventh Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso (1708–57), experienced civil war and the establishment of Chinese Manchu suzerainty over Tibet. The eighth, Jampel Gyatso (1758–1804), saw his country invaded by Gurkha troops from Nepal but defeated them with the aid of Chinese forces.

The next four Dalai Lamas all died young, and the country was ruled by regents. They were Lungtog Gyatso (1806–15), Tsültrim Gyatso (1816–37), Kedrub Gyatso (1838–56), and Trinle Gyatso (1856–75).

The 13th Dalai Lama, Tubten Gyatso (1875–1933), ruled with great personal authority. The successful revolt within China against its ruling Manchu dynasty in 1912 gave the Tibetans the opportunity to dispel the disunited Chinese troops, and the Dalai Lama reigned as head of a sovereign state.

The 14th in the line of Dalai Lamas, Tenzin Gyatso, was born Lhamo Thondup in 1935 in China of Tibetan parentage. He was recognized as the incarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1937, enthroned in 1940, and vested with full powers as head of state in 1950. He fled to exile in India in 1959, the year of the Tibetan people's unsuccessful revolt against communist Chinese forces that had occupied the country since 1950. The Dalai Lama set up a government-in-exile in Dharmsala, India (known as "Little Lhasa"), in the Himalayan Mountains. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in recognition of his nonviolent campaign to end Chinese domination of Tibet. He has written a number of books on Tibetan Buddhism and an autobiography.

The Panchen Lama is the second highest ranking figure in the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama. The Panchen Lama bears part of the responsibility for finding the incarnation of the Dalai Lama and vice versa.

The current Dalai Lama identified Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th reincarnation of the Panchen Lama on May 14, 1995. The People's Republic of China did not recognize this choice, naming Gyancain Norbu to the office of Panchen Lama instead. The whereabouts of the original Panchen Lama are currently unknown. Many observers believe that upon the death of the current Dalai Lama, China will direct the selection of a successor, thereby creating a schism and leadership vacuum in the Tibetan independence movement.

You will only receive emails that you permitted upon submission and your email address will never be shared with any third parties without your express permission.